Why having a mentor is important, especially for minorities, according to LinkedIn's Senior Director of Corporate Communications Andrew McCaskill:

- According to LinkedIn data, an estimated 60% of Black and Latino professionals do not have a mentor.

- Minority groups need advice on how to navigate spaces and work cultures where they have often not been listened to, McCaskill says.

- With the guidance of a mentor, you get to rehearse the biggest moments in your career before prime time.

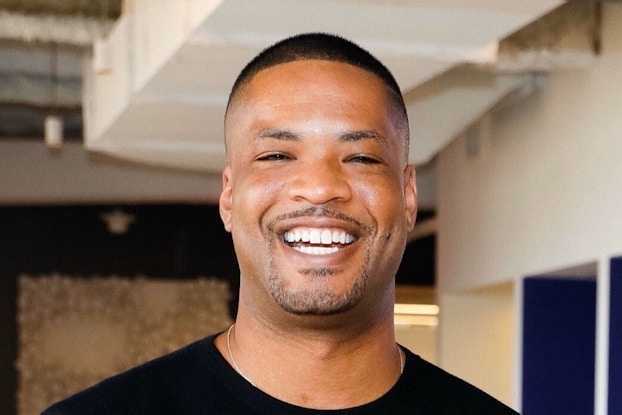

Andrew McCaskill is a LinkedIn Career Expert and Senior Director of Corporate Communications at LinkedIn. He helps advance innovative talent practices and diversity inclusion and belonging (DIB) strategies that help companies prepare for the future of work. McCaskill is also the author of a monthly LinkedIn newsletter, "The Black Guy In Marketing," where he offers career resources for professionals of color, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community like himself to help them successfully break through at work and beyond.

Before joining LinkedIn, McCaskill led the diversity and inclusion strategy for the global sales, marketing, and public affairs function at Facebook and U.S. consumer marketing and global communications at Nielsen. While at Nielsen, he led communications for Nielsen China, was named one of PR Week's Top 40 Under 40 PR Executives, and co-authored the award-winning Diverse Intelligence Series on the economic and cultural impact of multicultural consumers. Called a diversity champion by Fortune magazine, he also served as the Global Executive Sponsor for Nielsen's LGBTQ employee business groups all over the world.

Interested in a small business membership?

Find out how the U.S. Chamber of Commerce can help your company grow and thrive in today's rapidly-evolving business environment. Connect with our team to learn how a small business membership can benefit your bottom line and help you achieve your goals.

McCaskill tells CO— how mentorship has shaped his career and why he believes in planting seeds instead of mining for diamonds.

CO—: Who have your mentors been?

AM: My mentors are like my personal board of directors. One of my very first mentors was [former fintech and aerospace executive] Vijay Balakrishnan, who was a client during my early tech public relations (PR) days. Vijay once told me: "Relationships will save you sometimes when results won't." That shifted my ability to manage client situations. It shifted how I thought about my role as an adviser to people who were more senior, more experienced, and more wealthy.

The other mentor who really shaped my career was Glen Hauenstein, President of Delta Airlines, whom I met on a Delta flight. When I took over as Senior Vice President at Nielsen, Glen mentored me on how to think about my role in the larger enterprise.

My final mentor is Alicia Thompson, a Black woman who has had a storied career in PR. She has always been transparent with me about both her wins and her losses. She told me not just how she won, but she talked to me about mistakes that she made, so I could avoid making them.

CO—: What's the best piece of advice you have received from a mentor?

AM: Glen had always told me that working for global companies meant thinking with a global mindset. The sun does not rise in Manhattan and set in San Francisco.

When I was working at Nielsen, I got an opportunity to take over as the communications lead for Greater China, which included mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, the most profitable region for our business. I was to go to Shanghai, renegotiate our contracts on the ground, reorganize the communications function, and recruit and train my replacement. I'm a Black boy from a dirt road in Mississippi. I do not speak any Mandarin. Nielsen said, "We'll give you the support you need, you'll be able to figure it out."

I talked to Glen and he urged me to take the opportunity. So I moved to Shanghai and did everything that the company asked me to do in about 11 months instead of 18. To this day, people ask me about my experience in China. I would not have had the opportunities that I've had had I not taken his advice.

One of the greatest pieces of career advice I got was from someone who did not agree to be my mentor, an executive at Coke, Ingrid Saunders Jones. I interned there and had been hired as a contract employee for my last year of college. I knew Ms. Jones had other mentees who were young Black professionals at Coke and I wanted to be one of them. When I gave her my stump speech, she said, "I'm overextended, and I want you to have a mentor who can truly invest in you. But why did you ask me to be your mentor?" I said, "Because you're amazing." She responded, "Because I'm Black?" I said, "You're amazing and you're Black." And she said, "You cannot wait until you find a Black executive to be your mentor. You need to find a mentor no matter what their gender or ethnicity is who's doing the things that you want to do and helps you understand how to excel in that world."

That was freeing. She took off the blinders and the handcuffs. And it opened the aperture for me to be able to look at this whole thing differently.

[Read more: Execs From PepsiCo and Macy's to Salesforce Reveal Their Mentors' Best Advice]

I give them perspective; I don't necessarily give them advice. I try to talk to them a little bit about not work-life balance but work-life cohesion.

CO—: What characteristics make your mentors especially good?

AM: Great mentors give you context, and they give you confidence so I could ask the dumb questions and they would say, "Well, that's not actually dumb." Or "I wouldn't say it that way."

So much of the biggest moments in our careers are performance art. Mentors give you an opportunity to rehearse those big moments in your career and that's what my mentors are giving me.

CO—: Why is mentoring important for minority groups?

AM: For people from underrepresented groups or people who are immigrants, it's never the work or our work ethic that holds us back. More often than anything else, it's getting people to see us. It's decoding culture on how to go into spaces where we're the first or the only minority. We're trying to figure out how to be as much as of ourselves but also how to win in that culture. Mentors help us see that.

CO—: How has your relationship with your mentors and mentorship itself evolved over the years?

AM: I've always believed that great careers are a team sport. Many people roll off your board of directors. But you maintain those relationships, even if the nature of the relationship is different.

So much has changed now in how we engage with people. Part of the beauty of the digital revolution is that I could have a mentee in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, or Jacksonville, Florida. You don't have to be in Manhattan to meet or to engage with an executive in media. Technology has taken some of the guardrails down. We now have to give ourselves permission to reach out.

[Read more: Execs From Hershey's to Microsoft Reveal Their Mentors' Best Advice]

CO—: How has your experience shaped your perspective regarding mentoring? Are you mentoring others?

AM: I mentor a number of folks and usually pick them based on their own enthusiasm and ambition and who also know a little bit about how I think about giving back. Because then I know there's a little bit of like-mindedness there.

I give them perspective; I don't necessarily give them advice. I try to talk to them a little bit about not work-life balance but work-life cohesion.

Mentorships are also about reciprocity. I always coach my mentees to ask their other mentors, "You have done so much for me. Is there anything I can do for you?" I want to be a farmer and not a miner. I don't want to just take the diamonds and run. I want to plant seeds and grow and share the fruit with people.

CO— aims to bring you inspiration from leading respected experts. However, before making any business decision, you should consult a professional who can advise you based on your individual situation.

CO—is committed to helping you start, run and grow your small business. Learn more about the benefits of small business membership in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, here.