The economy had a wild ride in 2020. It is worth a look back at a year that will certainly be one for the economic history books.

It is easy to forget, given all that has happened since, that the economy was in good shape at the beginning of 2020. Economic growth was tracking around 2% even into late March. The labor market had added 214,000 jobs in January and 251,000 in February. Those are big numbers considering we were almost 11 full years into an economic expansion that had begun in June of 2009 – the tail end of the financial crisis. Had it not been for the COVID-19 virus, the economy would have continued to grow. As it is, at almost 11 years, the late expansion is the longest in the post-World War II era.

The two biggest factors slowing economic growth in February were Boeing’s trouble with the 737 MAX and the little-understood virus raging in Wuhan, China. Boeing’s troubles and the virus that would come to plague the rest of the globe were shaving a small fraction off of growth. At the time, the virus’ impact was due to shipping and supply chain disruptions. Forecasters widely assumed that the lost growth would be made up in the second quarter as China opened back up and Boeing got production of the MAX going again.

Once COVID-19 hit our shores though, it sent the economy into a tailspin from which it has yet to fully recover. The virus forced us into “The Great Pause” from mid-March until June. The Great Pause was the suspension of normal economic activity for both families and businesses. Government mandates, such as stay-at-home orders and forced business closures, and the general public's reluctance to engage in their normal activities drove the pause.

From tracking at near 2% growth in late March, the economy dropped rapidly. In March and April, more than 22.1 million Americans lost their jobs. Just two weeks of suspended economic activity (from mid-March to the end of the month) was enough to cause the economy to contract by 5% in the first quarter. The continuation of that suspension in April, May, and into June caused the economy to contract more than 31% in the second quarter.

The 31% drop is a record that we will hopefully never break. The previous quarterly contraction record was 10% – a mark the COVID-economy eclipsed by three-fold. Perhaps not surprisingly, that contraction was caused by the flu pandemic that year.

The economy roared back in a big way by a combination of lower case rates, the end of government-mandated closures, and the willingness of people to resume more of their normal routine. It grew more than 33% in the third quarter. This is a testament to the incredible resiliency of the U.S. economy.

Although that growth was greater to the upside than the contraction the previous quarter, the economy was still almost $700 billion smaller at the end of the third quarter than at the end of 2019. It is still more than $400 billion smaller now. It will not return to its pre-pandemic size until later this year – hopefully by the second quarter.

The recovery has been uneven. Some industries have more than recovered, especially those whose products are more in demand during a pandemic – technology for instance. Others that cannot operate fully, or at all, in a socially distanced manner, like restaurants, bars, travel, tourism, accommodations, and events continue to struggle. This split-recovery has become known as the “K-shaped” recovery. Those that recovered are the top of the “K” and those that have not are at the bottom.

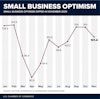

From the start of the pandemic in March through the end of the year, we chronicled what was happening in the economy with frequent posts about the latest economic data. Most of those posts included charts. Below you can see a compilation of some of the most interesting ones.

As you view the charts you will see how far the economy has come. Keep in mind the outlook for 2021 is strong because the pandemic will end this year. Vaccines will drive down cases and allow those business at the bottom of the “K” to finally begin to recover.

About the author

Curtis Dubay

Curtis Dubay is Chief Economist, Economic Policy Division at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. He heads the Chamber’s research on the U.S. and global economies.